Written for Daily Hive by Bowinn Ma, MLA for North Vancouver-Lonsdale.

“A developed country is not a place where the poor have cars. It’s where the rich use public transportation.” ― Gustavo Petro

I want to see rapid transit to the North Shore.

I want this as someone who used to spend 2.5 hours commuting daily back and forth across the Burrard Inlet in my previous career, as someone who has an academic background in transportation engineering, and as a local MLA who has heard from countless North Vancouver residents who are desperate for more choices in how they get around.

Ever since former City of North Vancouver Mayor Darrell Mussatto announced his visionary proposal for SkyTrain to the North Shore, there has been growing excitement among residents here about the potential of rapid transit — and for good reason.

If you live or work here, you’ll already know that traffic is a big deal on the North Shore and we are at a breaking point.

This brings me to the Main-Marine B-Line.

The Main-Marine B-Line is arguably the most significant public transit service improvement for the North Shore since the introduction of the SeaBus, which was spearheaded by the BC NDP Dave Barrett Government in the 1970s.

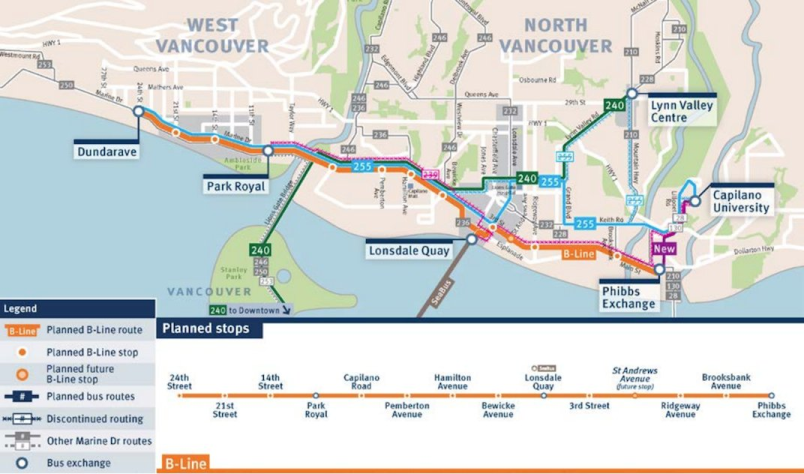

As a fast, frequent, and reliable transit connection linking West Vancouver to North Vancouver along a major east-west route, the Main-Marine B-Line from Phibbs Exchange through to Dundarave is expected to be within walking distance of 25% of all North Shore residents, 40% of all North Shore jobs, and 35% of all planned North Shore growth.

A graph shows the route of the proposed Main-Marine B-Line service that would connect West Vancouver and North Vancouver.

It is the first of three planned North Shore B-Lines, and a critical piece in the plan to improve mobility for people who commute throughout the region.

B-Lines are high-capacity vehicles that service a select number of major stops along a given route. Making use of transit-priority measures to ensure efficient service, they come often enough that transit-users don’t need to worry about how long they’ll have to wait for their next bus to arrive. This means busses running every 8 minutes during peak hours between Phibbs Exchange and Dundarave.

If this sounds a lot like rapid transit-lite, that’s because (effectively) it is.

B-Lines have served as precursors to many rapid transit lines in Metro Vancouver: Long portions of the 99 B-Line were replaced by the Millennium Line and will further be replaced by the Broadway Subway project; the 98 B-Line was replaced by the Canada Line; the 97 B-Line was replaced by the Evergreen Line.

As those routes gained ridership and communities demonstrated a commitment to choosing public transit over their personal vehicles, so came greater investments in service and the establishment of rapid transit lines to keep up with demand.

As public transit funding comes from Metro Vancouver as a whole, and infrastructure upgrades inevitably require support from provincial and federal governments, being able to make the case for where regional dollars should be spent is critical leverage local governments need to have around the Mayors Council table.

With that in mind, this Marine-Main B-Line has the potential to be transformative: in the short term for commuters; in the long term as an important demonstration of our growing readiness for higher forms of rapid transit.

Last year, I initiated and led the highly collaborative Integrated North Shore Transportation Planning Project (INSTPP, pronounced “in-step”). INSTPP is an unprecedented multi-agency, multi-level collaborative effort to produce a transportation action plan on the North Shore. Its report included recommendations to provide the Main-Marine B-Line with transit priority measures, to accelerate the implementation of the next two B-Lines, to develop new express bus routes, and to evaluate a rapid transit connection to the North Shore.

Because of INSTPP, TransLink is now evaluating a rapid transit connection to the North Shore as part of its update to their Regional Transportation Strategy. It’s a promising advancement for the North Shore, but an early one for which momentum must be maintained and local community commitment must be demonstrated.

It is in this context that opposition to the B-Line in West Vancouver and calls for the route to be truncated from Dundarave to Park Royal should be very concerning for residents throughout the North Shore. While it may be tempting for those of us in North Vancouver to wave off West Vancouver’s fight against transit priority measures as being unrelated to us, a collective failure to support a successful B-Line service substantially reduces our ability to justify to the rest of Metro Vancouver that the North Shore is ready to have their next two B-Lines accelerated, let alone ready to discuss rapid transit.

The North Shore has been waiting a long time for these kinds of regional transit investments to come from TransLink, the province, and the feds. We would be wise to carefully consider what might become of our rapid transit dreams if we insist on looking a gift bus in the grill.