Brent Richter, North Shore News – September 13th, 2018

North Vancouver-Lonsdale NDP MLA Bowinn Ma spearheaded the Integrated North Shore Transportation Planning Project, or INSTPP, earlier this year. After months of planning, a 35-page report was released Sept. 13. photo Lisa King, North Shore News

“We know things are bad – worse than bad. They’re crazy. It’s like everything, everywhere is going crazy, so we don’t go out anymore. We sit in the house, and slowly the world we are living in is getting smaller.’” – Howard Beale, from the film Network (1976)

Beale wasn’t talking about transportation on the North Shore, but you’d be forgiven for thinking that he was.

You can expect to hear a lot more about our now infamous traffic problems in the run-up to the Oct. 20 municipal elections as would-be mayors and councillors try to sell their plans to a frustrated public. But behind the scenes, for much of the last year, experts have been toiling away on a first-of-its-kind project meant to address the North Shore’s transportation woes.

A plan called INSTPP

Early in 2018, North Vancouver-Lonsdale NDP MLA Bowinn Ma gathered elected officials and expert staff from the three North Shore municipalities, two first nations, all four North Shore provincial ridings and one federal riding as well as TransLink, Vancouver Fraser Port Authority and Ministry of Transportation and Infrastructure staff, and got them into one room for a series of meetings – the Integrated North Shore Transportation Planning Project, or INSTPP.

For their research, they relied on census data, traffic counts from roads and highways, TransLink passenger trip logs, and the data Google collects from people’s smartphones to show real-time traffic speeds.

The INSTPP working group released their report on Thursday and will present their findings at the regular meeting of council in all three of the North Shore’s municipalities Monday evening.

“This is from the planners and the engineers. They’ve done all the hard work and the analysis to tell us at the political level – this is how you move the needle, this is how we move forward as a region in terms of transportation,” Ma said. “Now it’s our move as the politicians and the elected officials to start talking to each other about how we actually get these done. The benefit of having this document is now we’re talking about just what’s in this document as opposed to the 270 ideas that were previously on the table and floating up in the air.”

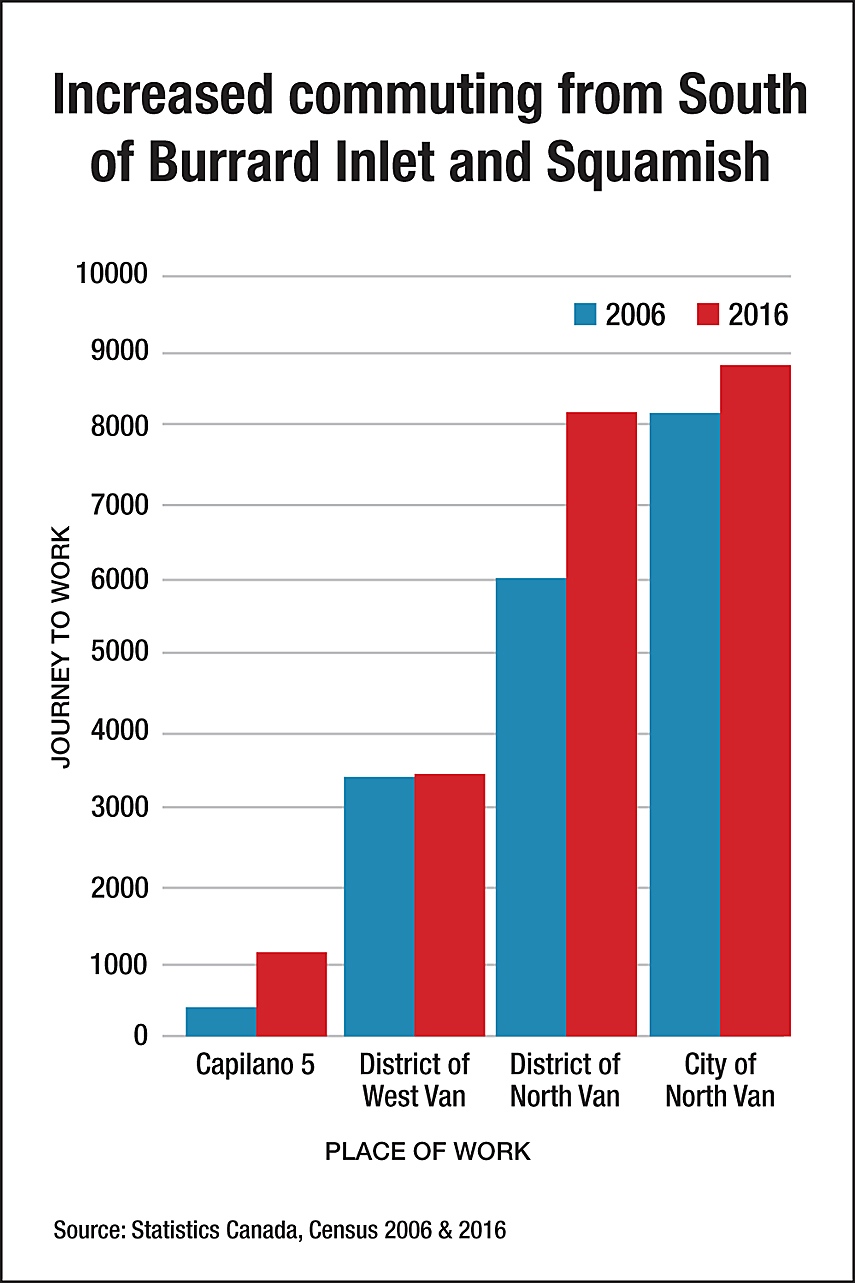

More people are commuting to North Vancouver for work now than 10 years ago, according to the latest census data. graphic Myra McGrath, North Shore News

Where things went wrong

The researchers arrived at five rough problems unique to the North Shore that either cause or exacerbate long commutes. First among them is how utterly dependent we are on the single-occupancy vehicle, largely thanks to our past land use decisions.

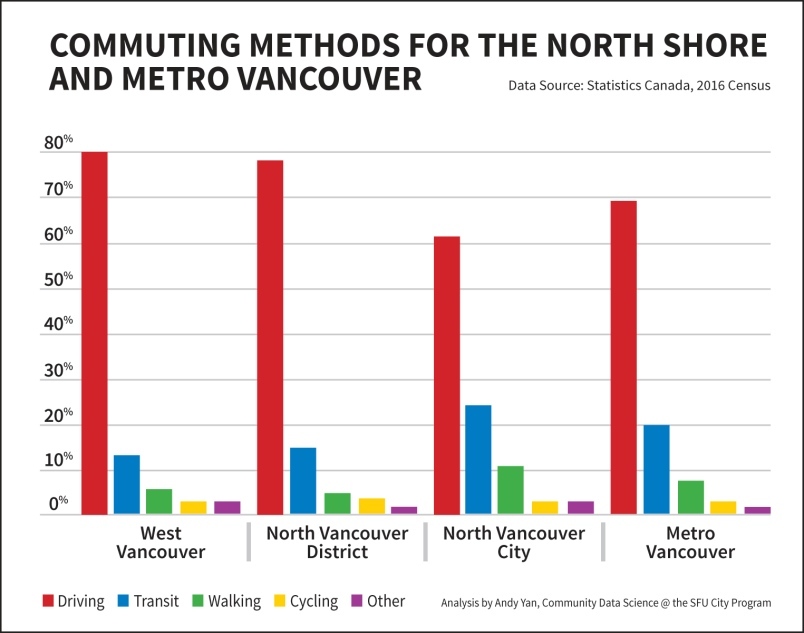

In West Vancouver and the District of North Vancouver, 77 per cent and 78 per cent of commutes, respectively, are done in personal autos. Less than a third of North Shore residents live within 400 metres or a five-minute walk from a frequent transit network, compared to 50 per cent of residents across the region.

And despite the traffic, the car is still a more attractive option, with travel times to most destinations being significantly lower. West Van municipal hall to the District of North Van hall is 10 to 15 minutes in a car, compared to roughly 50 minutes by bus. Commuting from Brentwood in Burnaby to North Vancouver City hall takes 20 to 35 minutes by car, but the same trip is more than an hour by bus (and that’s assuming you don’t miss the 232, which runs only every 30 minutes.)

No secret to anyone, the North Shore’s two bridgeheads are acute pinch points, the report confirms, but demographic and labour trends indicate the problem is getting worse.

It’s a commonly held belief that local densification and development have caused our current transportation problems, but that’s not borne out by the evidence, said Geoff Cross, TransLink’s vice-president of transportation planning. The North Shore grew by only 3.3 per cent in the last census period compared to 6.5 percent across the region.

Between 2011 and 2016 there were 2,900 more people working on the North Shore but the population of working age (age 20 to 64) people only grew by 900.

“I think population is a really small part of it,” Cross said.

“A lot of this information is so counter-intuitive to what people feel in their day-to-day lives,” Ma acknowledged.

And North Shore drivers rely on Highway 1 for local trips at a rate far higher than our Lower Mainland neighbours. Almost a quarter of the cars on the Upper Levels Highway during the afternoon rush hour are not headed for either bridge, but rather, somewhere else on the North Shore. That compares to less than five per cent in Surrey or less than three per cent in Richmond.

“There are just not a lot of alternatives. The grid does not have very many options for east-west travel, both from a congestion perspective and from a reliability perspective. If something happens on either one of those main east-west corridors, whether it be Upper Levels or on Main and Marine, then you can have extreme congestion events,” said Cross. “It doesn’t have the same resiliency as places within the region where you have parallel routes that act as options for people.”

Lastly, the INSTPP report concluded, the North Shore is lacking the tools to manage demand for road use, such as more restrictive parking rules, or preferential parking for high-occupancy vehicles and car shares, carpool incentives, real-time messaging warning of traffic delays or mobility pricing.

There will be no third crossing

The INSTPP report wastes no time in making it clear that the “third crossing” long desired by armchair engineers is a non-starter – at least not in the form they fantasize about while grinding teeth and grinding gears in traffic.

The road networks on both sides of a new crossing would have to be totally rebuilt to accommodate more incoming lanes of traffic, otherwise the receiving streets would become immediately clogged. In both Vancouver and on the North Shore, there is no desire to begin expropriating expensive land to create more expensive highway infrastructure.

The same goes for widening either of the bridges, which is not technically possible given the structural limitations, or replacing either of the current ones with a wider option, Cross added.

“Expanding the bridge only floods more people into the receiving network so all the pipes would have to change,” Cross said. “That’s not within the objectives of the people on either side of Burrard Inlet. We’re already confined. Finding more road space in a fairly built-out environment is neither desirable nor feasible in many places.”

And even if it were possible, Ma warned people to be careful what they wish for. Part of the INSTPP report deals with a hypothetical new mega-bridge over the Second Narrows. Modelling done by the experts found only minimal and short-lived benefits.

“Even if you had a 10-lane bridge right now, the variability of your trip might be a little bit less but you’re not actually saving much time. You’re talking about a $3-billion bridge in order to save maybe four minutes of crossing time. And that won’t even last very long before you end up back where you are right now. You’ll be overloading your local road network… because more people are driving,” Ma said.

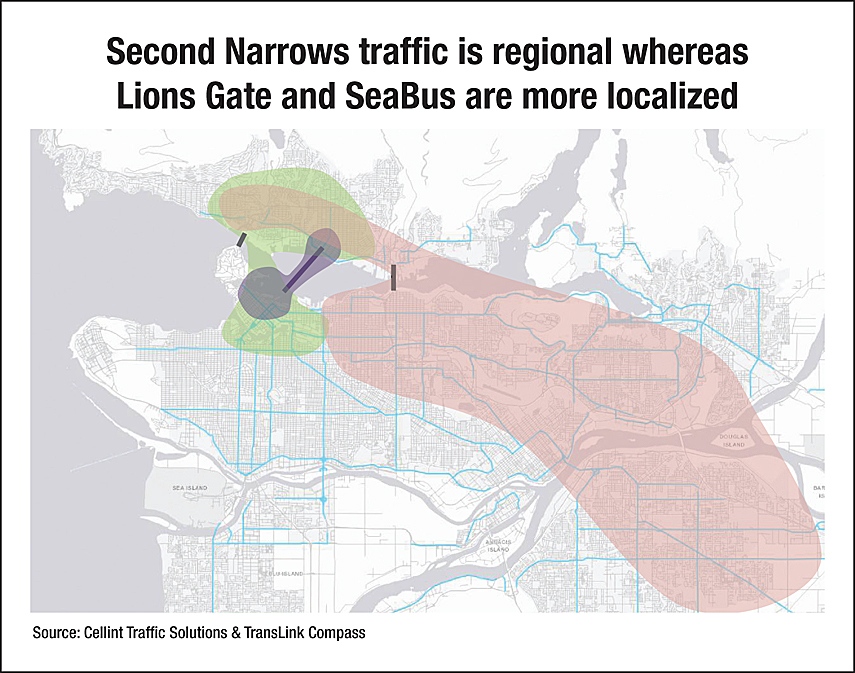

Traffic analysis shows that that Second Narrows Crossing is used by drivers from across the region while the SeaBus and Lions Gate Bridge support much more localized traffic. graphic Myra McGrath, North Shore News

The main goal of INSTPP, Ma said, is to get people from Point A to Point B, not necessarily their cars.

With so many more commuters arriving from the Fraser Valley, where they’ve been drawn to more affordable housing, one might think a rapid transit line to the east would woo people out of their cars. But that too doesn’t meet the feasibility test, as there still isn’t enough demand to justify the cost, Cross said.

“For rapid transit to work, it needs to work all the time. It’s not just commuter express service,” Cross said. “To justify all-day service for rapid transit, which is an order of magnitude more expensive to build, you need two-way traffic on the line all the time.”

Other flashy ideas examined but deemed not feasible or not worthwhile: Adapting CN’s rail bridge for transit and/or walking and cycling (the rail company has no plans to replace the bridge, and most of the time the bridge is in the raised position); and a gondola linking Phibbs Exchange to Capilano University (it would come at a high cost and would be no faster than taking a bus).

Here’s the plan to fix it

With all the downers out of the way, the INSTPP report does contain more than a dozen calls to action that can be taken in the near term. And a good number of them are already underway.

The three municipalities are already on the right track with their official community plans that concentrate growth in town centres where personal vehicles aren’t needed to access shopping, services and transit – but they should be completing and improving pedestrian and cycling networks, the report finds.

Cross described the Dundarave to Phibbs Exchange B-Line due to start running in the next year as the “lowest hanging fruit” when it comes to giving people a better east-west option than driving a clogged Marine Drive. With transit priority lanes, the trip could be done in 40 minutes – about 40 per cent faster than it takes on the bus now.

The SeaBus is also expected to move to 10-minute frequency during rush hour starting next year, part of the TransLink mayor’s council plan.

More B-Lines linking Cap U to Metrotown and Lynn Valley to downtown via Lonsdale are expected to start running sometime after 2022, but the group believes a new express bus from the SkyTrain system in Burnaby to Phibbs could be added to TransLink’s fleet sooner than that.

“We don’t think it’s a big-ticket item. It’s like how quickly could we do it? How do we collectively pay for it and try and advance in the next year or two?” Cross said.

The province, the District of North Vancouver and the federal government have committed to a $250-million project to overhaul the Ironworkers bridgehead interchanges, already under way, which INSTPP endorses but more work can be done to determine how buses can be given priority access to the bridgeheads.

The group is also advising the province to find a way to get stalls and crashes whisked out of the way faster than they are currently.

And, although they represent a small percentage of the traffic volume coming through the North Shore today, Squamish commuters should have access to a new regional bus to Metro Vancouver, the group recommends.

Residents of West Vancouver and the District of North Vancouver make nearly 80 per cent of their commutes by car, according to results from the latest census. graphic Myra McGrath, North Shore News

There is one major cement-and-asphalt construction project NSTPP is endorsing: a complete lower level road connecting West First Street in North Vancouver to Park Royal in West Vancouver. It also recommends investigating whether a Barrow Street to Dollarton Highway connection could be built, opening up new east-west options over the Seymour River.

And INSTPP doesn’t necessarily rule out rapid transit to the North Shore. At the request of the local mayors, TransLink will be including an analysis of a fixed-rail link from Lonsdale to downtown Vancouver in its next regional transportation strategy. Such a rail link would likely not have a big impact on bridge traffic, but it would likely have a high level of ridership, INSTPP noted. Similarly, the group recommended an update to a 2004 study into more cross-inlet ferry service in other neighbourhoods along the North Shore.

Because the high cost of housing results in more people commuting greater distances, the group advises the creation of a North Shore workforce housing strategy.

ISNTPP doesn’t expressly recommend that we adopt mobility pricing but it does advise the North Shore be an active participant in ongoing discussions and it does suggest the creation of a North Shore-wide program with schools and business to encourage “sustainable travel behaviour.”

Politically, charging people to drive during rush hour is one of the tougher sells, but persuading even a few people to avoid driving during peak times has big impacts for the whole road network, Cross said.

“If you reduce the volumes by five to 10 per cent, you can reduce the travel times by 30 per cent. There are real tip functions,” Cross said. “If you can shift two per cent more off of Lions Gate … you’ll get significant savings for everybody.”

We can’t stop now

Many of the action items produced in the 35-page report are simply to study ideas in more detail, rather than shovel-ready projects. That may sound anti-climactic for people crying out for relief, Ma concedes, but the most critical recommendation of all, in her mind, is creating a permanent intergovernmental committee to continue INSTPP’s work.

“I recognize that there may be members of the public who expect INSTPP to instantly give them a solution that they will feel tomorrow. Unfortunately, it’s just not that simple. What INSTPP does is provide us with a collaborative framework to move forward with. Without that, we can’t go anywhere,” she said.

And, Ma added, the fate of INSTPP recommendations will soon rest with three new municipal councils. Soon after the new councils and mayors are sworn in, they’ll have to decide whether to continue its work, or to revert to the way things used to be. Ma has already offered sit-down briefings with candidates running for mayor this fall to ensure they understand what’s at stake.

“The most important part of it is that we continue to work together. The fact of the matter is if each municipality went off in different directions advocating for different projects and different solutions, it’s very difficult for the region to mobilize resources from senior levels of government,” she said. “The work that INSTPP has created doesn’t provide value to the public unless all partners remain on board and committed to working with each other on this.”